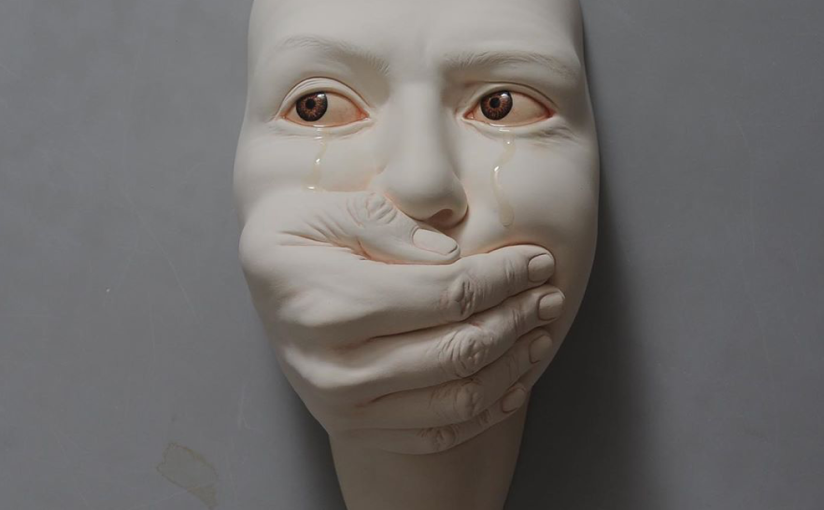

There is distraction and there is awareness. Distraction comes in its unlimited forms. Awareness, not so much. According to the Oxford English dictionary, distraction is defined as – “a thing that prevents someone from giving full attention to something else. A diversion or recreation.” It’s amusing and important to note how in the Romanian language, distracţie means distraction at the same time that it can be used to explain having fun – hai sa ne distrǎm. Etymologically, within both languages, distraction is interestingly associated to fun. Which would then imply, why is it not fun to distract oneself? What happens when we don’t ignore or don’t face certain things?

Observer J. Krishnamurti contemplates these existential questions in one of his interviews compiled in Total Freedom. He states:

“Most of us are aware of this emptiness, and we try to run away from it. In running away from it, we establish certain securities, and then those securities become all-important to us because they are the means of escape from our particular loneliness, emptiness or anguish. Your escape may be a master, it may be thinking yourself very important, and it, therefore, we cling to it desperately.”

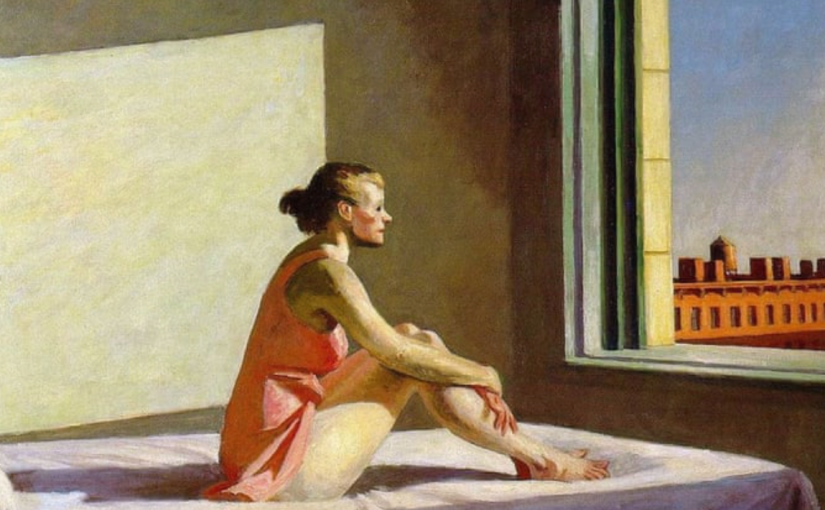

The global Covid pandemic is a perfect example of being forced to sit with oneself indoors when conflicting feelings of separation come up. One may feel distant especially in times when everything comes to a literal halt. When certain discomforting sensations come up, we either run away from it or distract ourselves with entertainment until even the entertainer can no longer put on the same show. YouTube and Netflix can only do so much before an individual once again sits with themselves in the unknown territory of uncertainty and confusion. However in the midst of all the delusions, there is still a uniting underlying thread. There is a oneness between all beings, at a sub-particle level. Nikola Tesla explains how feeling cut off early on in life resulted in developing introspection which helped him see and understand life much more vividly. When there is nothing stable externally, one can always find and develop the inner totem pole. He states:

“From childhood I was compelled to concentrate attention upon myself. This caused me much suffering, but to my present view, it was a blessing in disguise for it has taught me to appreciate the inestimable value of introspection in the preservation of life, as well as a means of achievement. The pressure of occupation and the incessant stream of impressions pouring into our consciousness through all the gateways of knowledge make modern existence hazardous in many ways. Most persons are so absorbed in the contemplation of the outside world that they are wholly oblivious to what is passing on within themselves. The premature death of millions is primarily traceable to this cause. Even among those who exercise care, it is a common mistake to avoid imaginary, and ignore the real dangers. And what is true of an individual also applies, more or less, to a people as a whole.”

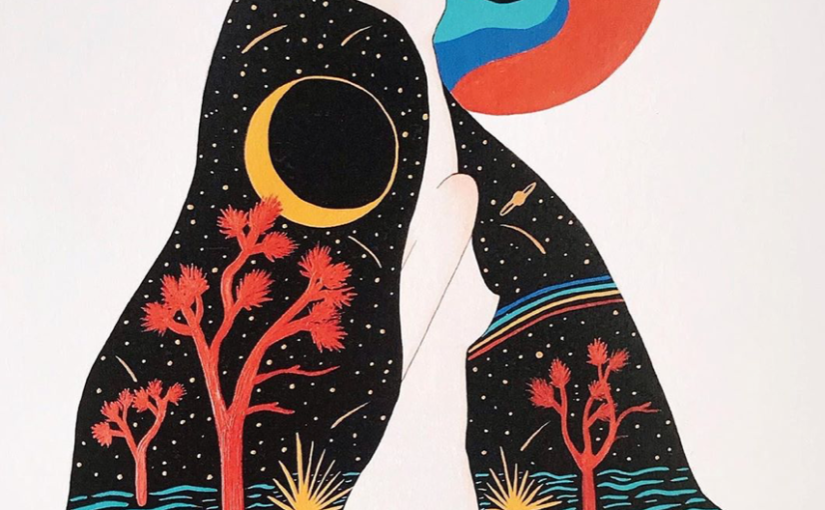

A shift in perception happens when one has the time to go into themselves deeper with no distractions. That’s when insights bloom, when we shift what’s out there from a refreshed internal perspective. There is no person out there for that person is you. There is no bird out there for that bird is also you. The wind. The mountains and hills. As the great English lecturer and observer, Alan Watts said:

“We do not “come into” this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean “waves,” the universe “peoples.” Every individual is an expression of the whole realm of nature, a unique action of the total universe. This fact is rarely, if ever, experienced by most individuals. Even those who know it to be true in theory do not sense or feel it, but continue to be aware of themselves as isolated “egos” inside bags of skin.”

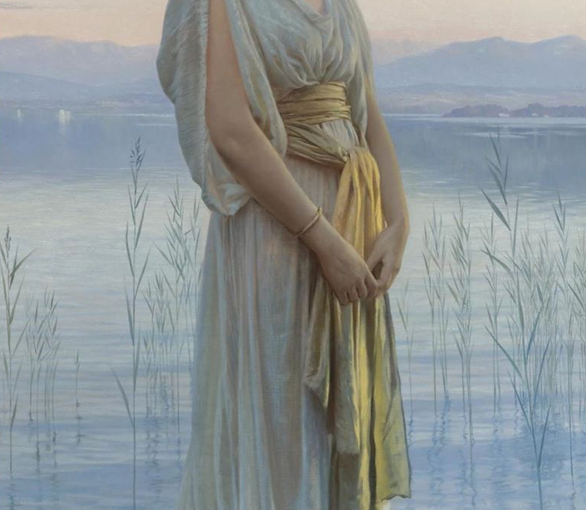

In the bare and naked stillness, we are forced to face the fragility of it all. That it’s just the ego which creates the division between external and internal. Facing the truth may be uncomfortable at first, but it ultimately provides the strongest foundation. What are ways in which you distract yourself? And how to you come back to your essence?